Time | January 27, 2025

One of the last things I understand when I’m putting a novel together is the structure of time. When does the story start and when does it end? Will it be linear or can it stutter and skip? At what point does our understanding of the action shift?

One of the last things I understand when I’m putting a novel together is the structure of time. When does the story start and when does it end? Will it be linear or can it stutter and skip? At what point does our understanding of the action shift?

—Ann Patchett, “These Precious Days”

The chapter | November 15, 2024

Like the momentary lifting of a pianist’s fingers while a chord still resonates, the classic novelistic chapter evokes time by dwelling in a pause rather than a strong ending. We feel time in the novel by marking it out into bits, but only bits that have no strong shape, that fade or blur into one another in the recollection. The greatest practitioners of the chapter have preferred to cast their divisions as fleeting caesuras with lingering aftereffects, scarcely memorable in their specifics but tenacious in the feeling they evoke. Situations yielding silently to new configurations, feelings fading imperceptibly or stealing upon us, shifts in the atmosphere around us: time in the novel is made up of these chromatic transitions, and the usual name for them in the history of the form is the chapter.

—Nicholas Dames, “The Chapter: A History,” The New Yorker, October 29, 2014

Form | April 3, 2024

Each novel must invent its own form. No recipe can replace this continual reflection. The book makes its own rules for itself, and for itself alone. Indeed the movement of its style must often lead to jeopardizing them, breaking them, even exploding them. Far from respecting certain immutable forms, each new book tends to constitute the laws of its functioning at the same time that it produces their destruction.

—Alain Robbe-Grillet, For a New Novel: Essays on Fiction, 1989; trans. Richard Howard

Elmore Leonard’s 10 rules for writing fiction | January 28, 2024

10. Try to leave out the parts that readers tend to skip.

Leaving room | December 27, 2023

I’m beginning to feel that if you create something you’re killing a lot of other things. And the way I write, since I do leave out most of the connections, and very little is pinned down, I feel that I’m doing a minimum of damage to other possibilities that might arise in a reader’s mind. The authors I dislike most or find unreadable are those who are forcing a personality on me that I don’t really care very much for in the first place. And they also tend to be the writers who are completely exhaustive about whatever it is they’re writing about until you’re just left feeling, “O.K., you’ve nailed me to the chair, that’s it, there’s nothing left to think about, there’s nothing to question.”

—Edward Gorey to Stephen Schiff, “Edward Gorey and the Tao of Nonsense,” The New Yorker, November 9, 1992

Eudora Welty is listening | December 13, 2023

Ever since I was first read to, then started reading to myself, there has never been a line read that I didn’t hear. As my eyes followed the sentence, a voice was saying it silently to me. It isn’t my mother’s voice, or the voice of any person I can identify, certainly not my own. It is human, but inward, and it is inwardly that I listen to it. It is to me the voice of the story or the poem itself. The cadence, whatever it is that asks you to believe, the feeling that resides in the printed word, reaches me through the reader-voice. I have supposed, but never found out, that this is the case with all readers — to read as listeners — and with all writers, to write as listeners. It may be part of the desire to write. The sound of what falls on the page begins the process of testing it for truth, for me. Whether I am right to trust so far I don’t know. By now I don’t know whether I could do either one, reading or writing, without the other.

My own words, when I am at work on a story, I hear too as they go, in the same voice that I hear when I read in books. When I write and the sound of it comes back to my ears, then I act to make my changes. I have always trusted this voice. …

Long before I wrote stories, I listened for stories. Listening for them is something more acute than listening to them. I suppose it’s an early form of participation in what goes on. Listening children know stories are there. When their elders sit and begin, children are just waiting and hoping for one to come out, like a mouse from its hole.

It was taken entirely for granted that there wasn’t any lying in our family, and I was advanced in adolescence before I realized that in plenty of homes where I played with schoolmates and went to their parties, children lied to their parents and parents lied to their children and to each other. It took me a long time to realize that these very same everyday lies, and the stratagems and jokes and tricks and dares that went with them, were in fact the basis of the scenes I so well loved to hear about and hoped for and treasured in the conversation of adults.

My instinct — the dramatic instinct — was to lead me, eventually, on the right track for a storyteller: the scene was full of hints, pointers, suggestions, and promises of things to find out and know about human beings. I had to grow up and learn to listen for the unspoken as well as the spoken — and to know a truth, I also had to recognize a lie.

—Eudora Welty, One Writer’s Beginnings

Vonnegut’s rules of style | December 1, 2023

1. Find a Subject You Care About. And which you in your heart feel others should care about. It is this genuine caring, and not your games with language, which will be the most compelling and seductive element in your style.

I am not urging you to write a novel, by the way — although I would not be sorry if you wrote one, provided you genuinely cared about something. A petition to the mayor about a pothole in front of your house or a love letter to the girl next door will do.

2. Do Not Ramble, Though. I won’t ramble on about that.

3. Keep It Simple. As for your use of language: Remember that two great masters of language, William Shakespeare and James Joyce, wrote sentences which were almost childlike when their subjects were most profound. ‘To be or not to be?’ asks Shakespeare’s Hamlet. The longest word is three letters long. Joyce, when he was frisky, could put together a sentence as intricate and as glittering as a necklace for Cleopatra, but my favorite sentence in his short story ‘Eveline’ is just this one: ‘She was tired.’ At that point in the story, no other words could break the heart of a reader as those three words do.

Simplicity of language is not only reputable, but perhaps even sacred. The Bible opens with a sentence well within the writing skills of a lively fourteen-year-old: ‘In the beginning God created the heaven and earth.’

4. Have the Guts to Cut. It may be that you, too, are capable of making necklaces for Cleopatra, so to speak. But your eloquence should be the servant of the ideas in your head. Your rule might be this: If a sentence, no matter how excellent, does not illuminate your subject in some new and useful way, scratch it out.

5. Sound Like Yourself. The writing style which is most natural for you is bound to echo the speech you heard when a child. English was the novelist Joseph Conrad’s third language, and much that seems piquant in his use of English was no doubt colored by his first language, which was Polish. And lucky indeed is the writer who has grown up in Ireland, for the English spoken there is so amusing and musical. I myself grew up in Indianapolis, where common speech sounds like a band saw cutting galvanized tin, and employs a vocabulary as unornamental as a monkey wrench. …

I myself find that I trust my own writing most, and others seem to trust it most, too, when I sound most like a person from Indianapolis, which is what I am. What alternatives do I have? The one most vehemently recommended by teachers has no doubt been pressed on you, as well: to write like cultivated Englishmen of a century or more ago.

6. Say What You Mean to Say. I used to be exasperated by such teachers, but am no more. I understand now that all those antique essays and stories with which I was to compare my own work were not magnificent for their datedness or foreignness, but for saying precisely what their authors meant them to say. My teachers wished me to write accurately, always selecting the most effective words, and relating the words to one another unambiguously, rigidly, like parts of a machine. The teachers did not want to turn me into an Englishman after all. They hoped that I would become understandable — and therefore understood. And there went my dream of doing with words what Pablo Picasso did with paint or what any number of jazz idols did with music. If I broke all the rules of punctuation, had words mean whatever I wanted them to mean, and strung them together higgledly-piggledy, I would simply not be understood. So you, too, had better avoid Picasso-style or jazz-style writing if you have something worth saying and wish to be understood.

7. Pity the Readers. They have to identify thousands of little marks on paper, and make sense of them immediately. They have to read, an art so difficult that most people don’t really master it even after having studied it all through grade school and high school — twelve long years.

So this discussion must finally acknowledge that our stylistic options as writers are neither numerous nor glamorous, since our readers are bound to be such imperfect artists. Our audience requires us to be sympathetic and patient teachers, ever willing to simplify and clarify, whereas we would rather soar high above the crowd, singing like nightingales.

That is the bad news. The good news is that we Americans are governed under a unique constitution, which allows us to write whatever we please without fear of punishment. So the most meaningful aspect of our styles, which is what we choose to write about, is utterly unlimited.

8. For Really Detailed Advice. For a discussion of literary style in a narrower sense, a more technical sense, I commend to your attention The Elements of Style by William Strunk, Jr. and E. B. White. E. B. White is, of course, one of the most admirable literary stylists this country has so far produced. You should realize, too, that no one would care how well or badly Mr. White expressed himself if he did not have perfectly enchanting things to say.

—Kurt Vonnegut, “How to Write with Style”

How a book starts | November 22, 2023

I remember he’d appear in quiet moments. You wouldn’t hear him, just see him. Tall and lanky in the corner. Or in the drawing room with a notebook. Scribbling away. Simply observing.

I remember he’d appear in quiet moments. You wouldn’t hear him, just see him. Tall and lanky in the corner. Or in the drawing room with a notebook. Scribbling away. Simply observing.

Isn’t that how it starts? said Margaret.

What?

A book.

Yes. I suppose so.

All those little moments that nobody else notices. Little sacred moments of the everyday. She picked up her camera (click). Like that moment (click). Or that.

Good God, will you stop now, Margaret? What’s gotten into you?

—Sarah Winman, Still Life

What to keep | November 15, 2023

After we saw what there was to see

we went off to buy souvenirs, and my father

waited by the car and smoked. He didn’t need

a lot of things to remind him where he’d been.

Why do you want so much stuff?

he might have asked us. “Oh, Ed,” I can hear

my mother saying, as if that took care of it.

After she died I don’t think he felt any reason

to go back through all those postcards, not to mention

the glossy booklets about the Singing Tower

and the Alligator Farm, the painted ashtrays

and lucite paperweights, everything we carried home

and found a place for, then put away

in boxes, then shoved far back in our closets.

He’d always let my mother keep track of the past,

and when she was gone—why should that change?

Why did I want him to need what he’d never needed?

I can see him leaning against our yellow Chrysler

in some parking lot in Florida or Maine.

It’s a beautiful cloudless day. He glances at his watch,

lights another cigarette, looks up at the sky.

—Lawrence Raab, “After We Saw What There Was to See” from The History of Forgetting

Journal | November 3, 2023

At night it was easy for me with my little candle

to sit late recording what happened that day. Sometimes

rain breathing in from the dark would begin softly

across the roof and then drum wildly for attention.

The candle flame would hunger after each wafting

of air. My pen inscribed thin shadows that leaned

forward and hurried their lines along the wall.

More important than what was recorded, these evenings

deepened my life: they framed every event

or thought and placed it with care by the others.

As time went on, that scribbled wall — even if

it stayed blank — became where everything

recognized itself and passed into meaning.

—William Stafford, “Keeping a Journal”

Light | October 26, 2023

The older you get, the more light you need for reading. When you’re young you can read by low light or no light. At 60, you need around 100 watts.

Too much light is as bad as too little. Glare hurts your eyes.

Avoid high contrast. “What you want is a well-lit room where the reading area is illuminated by a generous, focused pool of light, and the surrounding area by comfortable ambient lighting.”

Translucent shades are best for reading.

Three-way bulbs (50/100/150) are most comfortable and useful.

A reading lamp should be placed to the side and slightly behind the reader. It can go on either side. “But to avoid the shadow of your arm while writing and reading simultaneously, a right-handed person should place the lamp on the left.”

—Elaine Louie, “Expert Advice on Selecting a Good Reading Lamp,” New York Times, April 10, 1986

Memory | October 18, 2023

It seemed to Marigold that you remembered things because they changed. You didn’t need to remember what was right in front of you.

—Louise Glück, Marigold and Rose: A Fiction

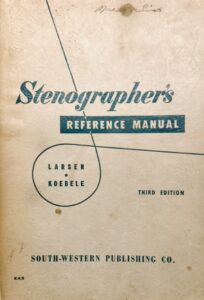

Punctuation, from my mother’s stenography manual | October 11, 2023

Punctuation is still in style. Picture punctuation as a set of marks essential to the reader’s correct interpretation of the writer’s thoughts. While the choice of punctuation marks in most instances is obvious, there are cases when the degree of separation determines the choice. Let different length bars represent the varying degrees of pauses obtainable by the use of punctuation marks:

. ! ? ————–Close of sentence

: ; ———– Stop within a sentence

, —— Breath stop

— —— Sudden break or change of thought

Marks of punctuation should not be inserted at the whim of the writer, but their use should be based upon accepted principles and a desire to make the meaning clear. The correct application of punctuation principles should become habitual and automatic. Good stenographers should avoid over-punctuation.

—Lena A. Larsen and Apollonia M. Koebele, Stenographer’s Reference Manual, 3rd ed. (Cincinnati: South-Western Publishing Co., 1949), 73.